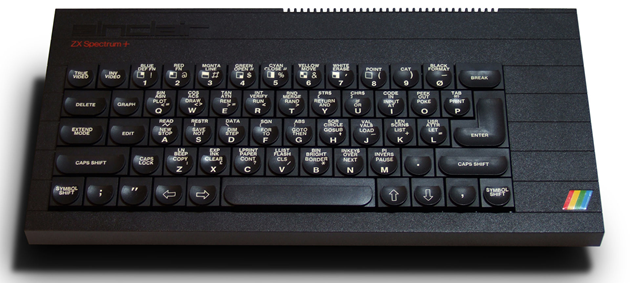

With the humble and much-loved Sinclair ZX Spectrum becoming 40 years old this year, Andrew Holland takes a look back at the machine – commonly and variously known as just a “Sinclair Spectrum”, “Spectrum” or even “Speccy” for short – what made it so popular and at the Spectrum’s legacy over the years since…

The birth of a classic

Launched on the 23rd April 1982 following the success of Sinclair Research’s previous ultra-low-cost computer – the ZX81 – a year earlier, the Spectrum was eagerly awaited by home computer enthusiasts of all ages and seen by some as the machine that would bring affordable colour home computing to the masses.

The late Sir Clive Sinclair was determined to steal a march over the much more expensive Commodore 64 and Acorn’s BBC Micro unveiled just months previously. Whereas Sinclair’s rivals were focused on producing powerful, sophisticated machines with their retail price not really being their prime consideration, Sir Clive was focused on producing a relatively powerful computer for a more modest price. In truth, a machine absolutely “built down to a price” for a mass market in the UK that just couldn’t afford one of the other market-leading machines.

With an initial asking price of just £125 or £175 (soon reduced to £99 and £129 a year later) for the 16K or 48K RAM models respectively, this quirky looking home computer with 15 colours, (rudimentary single-channel) sound generation abilities and possibly the second-worst keyboard ever fitted to any Sinclair machine (the ZX80 and ZX81 take the prize for the worst!), was not only a major upgrade and advance over the 1K RAM monochrome and mute ZX81 but also came in at a fraction of the cost of Commodore’s and Acorn’s much more capable machines (which cost between 2 and 4 times as much as the Spectrum).

Powered by the same low-cost Zilog Z80A processor as Sinclair’s previous two ZX machines, making it relatively easy for the nascent UK computer games industry to get to grips with quickly, the Sinclair Spectrum – in its various forms – sold in the order of 5 million units during a production run lasting 10 years and lead to the development of numerous clones, some of which are still in production today along with their associated and very active user communities.

Those 10 years were a testament to its enduring popularity, the thousands of software titles (admittedly mostly games, of course!) and the vast array of hardware add-ons produced for it from both Sinclair Research itself and the many “garden-shed” and professional software and hardware vendors alike who realised this was a machine well worth supporting.

Like the previous two machines, the original Spectrum was designed to only be connected to a standard TV via the antenna socket as it lacked a dedicated RGB monitor port (with all the associated picture quality issues that were produced compared to a dedicated monitor when you’re pushing a crisp computer-generated display output into a rough UHF modulator designed for rather lower grade fuzzier 625-line analog TV!), this again a clear sign of the “built to a price” mentality of Sinclair – few homes would have a computer monitor lying around but pretty much everyone had a TV they could use, either the main living room TV so as to annoy and frustrate your parents when they wanted to watch Corrie in the evenings or else a little portable TV if you were lucky enough to nag your parents into buying you one also!

Upgrading optionally

All ZX Spectrums had a single expansion port at the back which allowed for hardware expansion. With add-ons from simple joystick port interfaces (as early Spectrum’s lacked built-in joystick ports) to complex mass storage interfaces and even oddities like the Currah μSpeech, there was pretty much nothing that its more expensive rivals could do that the Spectrum couldn’t also be expanded to do.

Though it was true that some of this hardware left much to be desired in terms of quality and reliability, especially (and regrettably) that from Sinclair itself. Few who have ever used the optional (and initially relatively expensive at £49.95) curio that was the Sinclair ZX Microdrive will tell you that it was reliable, for it certainly was not!

The mini cartridges of looped tape that it used stored a nominal 90K when formatted and had – compared to cassette tape storage – a pretty quick 16KB/s transfer rate, putting it almost in the realms of floppy disk-like performance speed-wise. Sadly, this was not matched in terms of reliability as the ultra fast-spooled tape tended to stretch way too easily causing data loss sooner rather than later. Thus trusting anything to a microdrive cartridge was a leap of faith few were willing to make again after losing data that very first (or second!) time (myself included!).

Not to be put off, however, Sinclair’s attempt at instant-loading ROM game cartridges – to give the Spectrum a “games console” feel complete with dual joystick ports – via the ill-fated ZX Interface 2, sadly faired little better. Few games were ever produced on cartridge format for it and what few there were, were excessively expensive when compared to their otherwise identical tape-based versions. And I’m not even going to get into the ZX Printer and its rolls of oft-jamming thermal toilet paper!

Third-party hardware, however, generally tended to be better quality and many popular expansion devices did well, with Romantic Robot’s snapshot-creating Multiface perhaps being among the best known and most beloved by gamers and professionals alike. Sadly, I never owned one of those, darn!

We have all the time in the world to… load software from cassette!

If only due to its huge cassette back-catalog if not for the lack of reliability or availability of any other means, for most Spectrum owners, software was loaded from and saved to cassette tape via any standard mono cassette recorder (that you obviously had to buy separately or you already had from previously owning a ZX80 or ZX81, of course!).

The joy of sitting there waiting several minutes for a tape-based game to load is a “joy” that only people who lived through the home computing years of the 1980s can ever relate to and possibly recall being frustrated by. Let me be clear here, that 48K of memory took up to around 8 minutes to be completely filled up by loading from tape. So whenever you wanted to play another game, you had to pull the power cord out from the back and plug it in again (as there was no reset or power switch, another cost-saving!), and then type:

LOAD “”

on the keyboard, hit Enter and then press play on the cassette recorder to start the loading process. If you were lucky, up to 8 minutes or so later the game will have loaded after you (and your bemused and irked parents if they were with you) had endured the screeching and wailing sounds of the loading process as the original Spectrum had only an internal speaker with – yes, you guessed it – no volume control or mute button in sight!

If you think I’m just being a snowflake here and it really wasn’t that bad, then hey, let me not even try to convince you otherwise when there are plenty of videos out there on YouTube that can do it for me. Consider this one of the amazingly popular Jetpac and, as you watch this, keep in mind that this is merely a 16K game, 48k (and later 128K) games took proportionately much longer to load and dished out the same kind of aural racket while doing so – such as this 128K classic arcade conversion, Chase HQ!

Though at least with the 128K games, there was a way to shut them up as the 128K machines were devoid of an internal speaker, choosing instead to output their sound through the TV directly so you could turn the sound down to give your ears a rest – but more on the 128K machines below, I’m jumping ahead of myself!

Of course, as I said above, all this was truly indeed if you were lucky. Sometimes you wouldn’t be, the volume level might have been wrong or the tape damaged or the cat might have walked past at the wrong moment and nudged the ear jack connector at some point, and even if not, sometimes you’d get right to the end of the loading process and the Spectrum would either just crash needing you to try a highly-technical TIOAOA sequence or it would just reset by itself to the power-on screen. It’s why my generation has so much patience, frankly!

Despite the Spectrum’s quirks and faults it truly was an amazing piece of design on many levels. Not least, and in a very geeky way, in that it managed to squeeze a full-colour display out of just 0.75K more RAM than the ZX81 needed to use. It did this by – as you’ll probably have worked out by now – cutting corners to save money by only allowing 2 colours per 8×8 block of pixels.

The Spectrum had no dedicated hardware sprites or graphical processors, all graphics were – as was common back then – solely generated by the main processor and used main memory to do it. Its odd display arrangement lead to the infamous (and sometimes endearing) colour-clash where two graphical “characters” in a game of different colours met. This wouldn’t be a problem on other computers but on the Spectrum, it was and resulted in games where characters would take on their background or other character’s colours unexpectedly or else would simply be rendered in monochrome to avoid this effect happening at all.

But, to be frank, this quirk was yet another example of the Spectrum’s honest, down-to-earth simplicity and charm. It cost far less than its rivals and really, you couldn’t really expect it to perform as well as its rivals. Except that many still did nonetheless and it in no way blunted the desire of software houses to produce games for it who saw its technical limitations as a challenge to write better code to work around them. Graphical limitations aside, if you were gaming on a home computer in the 80s, there was a good chance it was on a Spectrum such were the numbers sold.

With that vast array of games – at one point the largest of any home computer during the 80s – it naturally became the home computer of choice in the UK for every kid that wanted to get into computer gaming without it costing their parents a small fortune. With games costing as little as £1.99 being sold in newsagents from the likes of Mastertronic and Firebird the humble spectrum took its place among its more expensive rivals in the playground wars that then ensued to the battle cries of “my computer is better than yours!” in schools across the land.

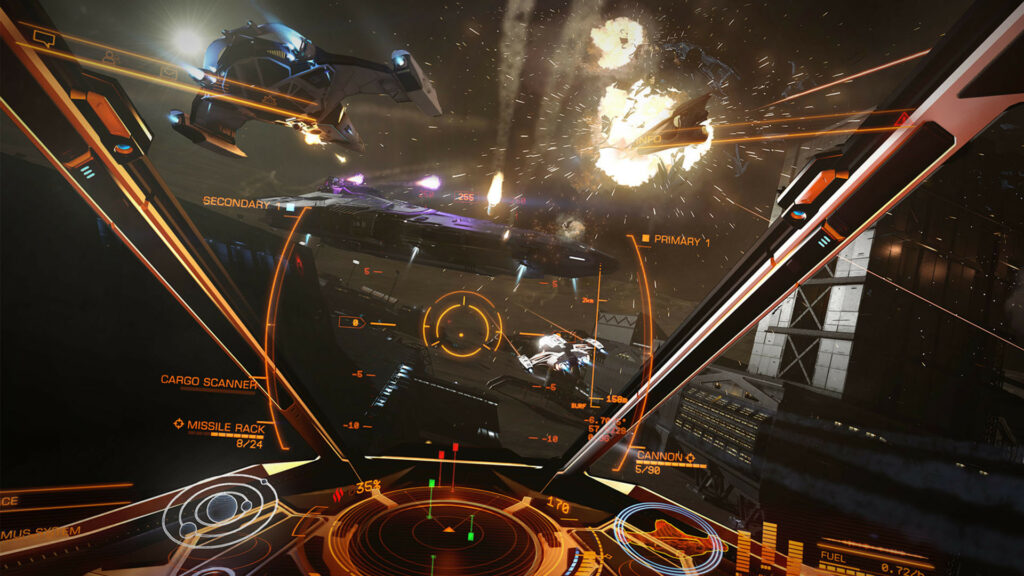

Underlining that success lead to games that were big on rival machines being ported to the Spectrum too, including legendary classics such as Elite (which started originally on the BBC Micro). Sure, it wasn’t quite as good-looking as the BBC Micro original but it was just as playable!

As a side note, Elite is oddly the only game from the Spectrum era that I still play regularly today, sort of. On the PC I am today a huge fan of Frontier Developments’ Elite Dangerous, itself a full-service multiplayer reimagining of the game for the modern age. When I have absolutely nothing else to do, rare though that is, I can sometimes be found plowing my trusty Python around space trading in goods, taking out the odd space pirate and occasionally being expensively ganked by the bad actual human players (I’m still learning how to beef up my ship so I can go on the offensive more but this game is so grindy, it’s not called Elite Dangerous for nothing!).

But let’s get back to the 80s, and I loved my 48K Spectrum (which I bought second-hand around 1985 to replace an outdated and mocked-by-friends ZX81!) and would spend hours at a time keying in program listings for games included as part of some of the many Spectrum-related monthly magazines of the era such as Sinclair Programs. Yes really, we actually did that!

Y’see, apart from loading commercial games from cassette tape you could also easily program the Spectrum using its built-in BASIC programming language – like most home computers of the time. No bloated compilers or development environments to install here, just power the Spectrum on, and immediately you’re in a BASIC interpreter. Just as I did, it lead so many of my generation to cut their programming teeth on home computers such as these and then end up following software engineering as their professional careers – once a love of programming has been established, it’s hard to give it up! So in some ways, I can say that without the Spectrums I owned as a kid, I’d probably had never become a programmer and later a software engineering lecturer!

There were pages and pages of code in magazines and kids would just sit around at evenings, weekends, and – if parents were really lucky – school holidays and type in a several pages-long listing for a game. Oh, we so knew how to rock back then, eh?! The illustration that went with the listing in the magazine usually showed a fancy and well-drawn spaceship or something equally as cool, but by the time you’d actually got the program finished and running – if it ran at all, sometimes you’d make a mistake that would render the whole thing useless and you’d spend hours hunting down the bugs – you’d see a little block that moved on the screen that vaguely resembled something like a spaceship.

And that little block moved very slowly because oh, the one thing you never knew before – but you do now – is that programs in Sinclair BASIC run very slowly compared to commercial software which was written not in any high-level language (such as BASIC) but in assembly instead, exactly for performance reasons! And writing assembly on a Spectrum is hard, proper hard. Don’t believe me? Take a look for yourself for a challenging and frustrating but rewarding experience!

But via coding in BASIC was simply how you interacted with the machine unless you had loaded a game or other software, such as a spreadsheet package or word processor perhaps – yes, this funny little machine could even be used for word processing, Tasword was used regularly for my college essays during the early 90s and I remember squinting at its irregular and cramped custom 64 characters per line display to this day on a 12″ B&W TV (the Spectrum had 32 characters per line by default)!

The more things change, the more they stay the same

Sadly, fun though all this was, as the decade wore on it was obvious to many that upgrades were needed to keep the Spectrum popular. First, Sinclair Research released a relatively minor update – the ZX Spectrum+ – which was little more than the same 48K Spectrum mainboard inside a new case sporting a new, QL-inspired proper keyboard and a reset button for the first time (I kid you not!). Costing £180 (reduced to £130 in 1985 when the original rubber-keyed machines were axed), inside it was exactly the same machine even if it looked like something rather fancier at first glance from the slick TV adverts put out for it at the time!

This obviously wasn’t going to be enough and while its replacement was launched first in Spain in 1985 (due to an agreement with Sinclair’s Spanish distributor Investrónica who also co-designed it with Sinclair), it wasn’t until 1986 that the UK saw the launch of the ZX Spectrum 128K.

With a huge black heatsink on the right-hand side on which to burn your wrist on a summer’s day, this machine earned the nickname “The Toastrack”. Priced at £180 and having the exact same graphics abilities and CPU as all of the previous Spectrums, it sported 128K of RAM, MIDI and RS232 ports, an RGB and composite monitor port, and an AY-3-8912 3-channel dedicated sound chip working alongside the existing Spectrum CPU-generated single sound channel. This meant that games could be written to take advantage of these new abilities but they would not be backward compatible with older spectrums.

The need for games to be coded to take specific advantage of the machine’s new features might have been a problem were it not that, thankfully, the Spectrum 128K was fully backward compatible with existing 16K and 48K software titles and hardware, so people moving to the new machine didn’t have to junk their existing games collection or add-ons, phew! For the remainder of the 80s and into the 90s it was common for games to be released for both 48K and 128K machines, there being very few 128K-only releases in recognition of the vast numbers of 48K Spectrums already sold.

Thus games often came on cassettes with two versions on them (one on either side) for 48K or 128K machines or else the loading was in several parts. The earlier part of the load was for the bulk of the game common to both machines and the later part was purely for the extra features of the 128K version. This made the Spectrum 128K truly the machine to have and owners mocked and laughed at their Spectrum 48K owning friends in the playgrounds. I finally upgraded to a Spectrum 128K by 1990, curiously swapping a second-hand Sinclair Pocket TV for it at that time via the Loot paper (at the time the place to obtain second-hand home micro stuff, or pretty much anything really!). In retrospect, while it was a great swap and I loved that Spectrum even more than my original 48K Speccy, I wished I hung onto that TV now. It would have been a great bit of retro-tech to have kept, albeit now totally useless since TV has long since gone fully digital!

Soon after the launch of the Spectrum 128K, a cash-strapped Sinclair Research saw Sir Clive sell the Sinclair brand name and rights to produce further ZX Spectrum models to Alan Sugar’s Amstrad and 1986 thus saw the launch of another new Spectrum, the +2, replacing the Spectrum 128K for around £140, Amstrad holding true to its promise of being able to make the Spectrum for a significantly reduced cost by shifting production to the far-east.

This was essentially the same machine as the Spectrum 128K but in another new case with an even better keyboard, two proprietary joystick ports (that annoyingly looked like standard Atari “D” ports but were wired differently meaning only official Sinclair sticks worked) and an integrated cassette deck (which annoyingly lacked a tape counter but even more so, still no bloomin’ power switch!). But no more would you need to faff around with an external tape deck, it should all just work straight away (and usually did)!

The following year saw one final new Spectrum launched, the +3 (and for cost reasons, a reworked +2 using the +3’s core internals, named +2A on screen but not on the case), to be sold alongside the +2A at an initial £249 (soon dropped to £199 however). The +3 was the first and only true Sinclair-branded Spectrum to feature a built-in floppy disk drive, with Amstrad opting for the relatively non-standard 3-inch drive as also used in Amstrad’s own rival computer, the CPC-6128. Amstrad was said to have used this drive over the much more common 3.5-inch drive for, unsurprisingly, cost reasons.

Other than the disk drive, the +3 offered little new over the +2 apart from a bunch of unfortunate bugs and incompatibilities as Amstrad’s redesign to incorporate the disk drive’s +3DOS operating system (and enable the new machine to optionally boot up in CP/M) along with other sundry changes and tweaks to the internal core design caused a small number of existing software titles and hardware to no longer operate correctly or at all. Most notable among these is the ZX Interface 1, thus rendering the ZX Microdrives unusable on the +3 (and +2A) despite remaining compatible with all previous Spectrums. This combined with a design defect that lead to garbled sound on early units, the dearth of titles produced on floppy disks and the relatively high cost compared to the otherwise equally-as-good +2 meant the +3 was never as successful as any of the previous machines and production of it ended in 1990.

But collectively the Spectrum 128K, +2, and +3 were relatively simple upgrades to what remained fundamentally an early 1980s design. With the age of 16-bit home computing arriving with the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga in 1985, it was viewed by many as too little, too late even at launch, even if all the 128K Spectrum models continued to stick to the original Sinclair values of undercutting other mainstream rivals and remaining easy to set up and use.

The +2 remained in production until 1992 when declining sales spelt the Spectrum’s demise (which by then was at revision +2B, apt for when this slightly Shakespeare-esq named model met with the slings and arrow of outrageous (mis)fortune by being canned!).

I carried on using my Spectrum 128K until the mid-90s during which time I had moved to the PC as my “go-to” computer for doing stuff in general and for playing games.

Over the years that followed I sadly lost that Spectrum and the huge collection of games I had for it but about a decade ago whimsy and a hawk-eyed scouring of eBay one day lead me to pick up a Spectrum +2 and some games, boxed in pretty good condition for a good price. I had to fix the keyboard on it and it currently

has some distorted sound issues that it didn’t have when I bought it, but otherwise still works well for a machine made in 1987 and occasionally puts in an appearance on campus at “end of year” weeks where I’ll boot up Pacmania on it and let befuddled students play a retro game on actual real hardware they’ve usually never seen before!

Those 10 years of production for what was pretty much the same machine, save for minor enhancements, and with the later machines mostly being backwards compatible with hardware and software from the early ones is an achievement in its own right and Sir Clive Sinclair should have been rightly proud of his achievement with this machine, even if he originally wanted the machine to be taken seriously as a “proper” computer not merely as a “games machine”.

But that those 10 years also lead to thousands and thousands of kids growing up in the 80s and early 90s to later seek careers in the computer hardware, software or gaming industry is further testament to the amazing success and endearing nature of the Sinclair Spectrum and the loyal following it engendered in millions of users, but this is not where the Spectrum story ends, not by a long way…

The Imitation Game

A computer as astoundingly popular as the Spectrum yet built on such relatively low-cost and simple hardware was inevitably going to be the subject of cloning, both officially and unofficially sanctioned by Sinclair or Amstrad.

The USA had the Timex Sinclair 2068 which while being an official Sinclair Spectrum for America was sadly mostly incompatible with original Sinclair Spectrum software without the use of emulation ROMs.

Likewise, Spain’s Investrónica had both the 48K Spectrum+ and Spectrum 128K, which they helped to localise for the Spanish market while by far and away it was the Soviet Union (and later Russia) that had the largest number of unofficial clones of any other country.

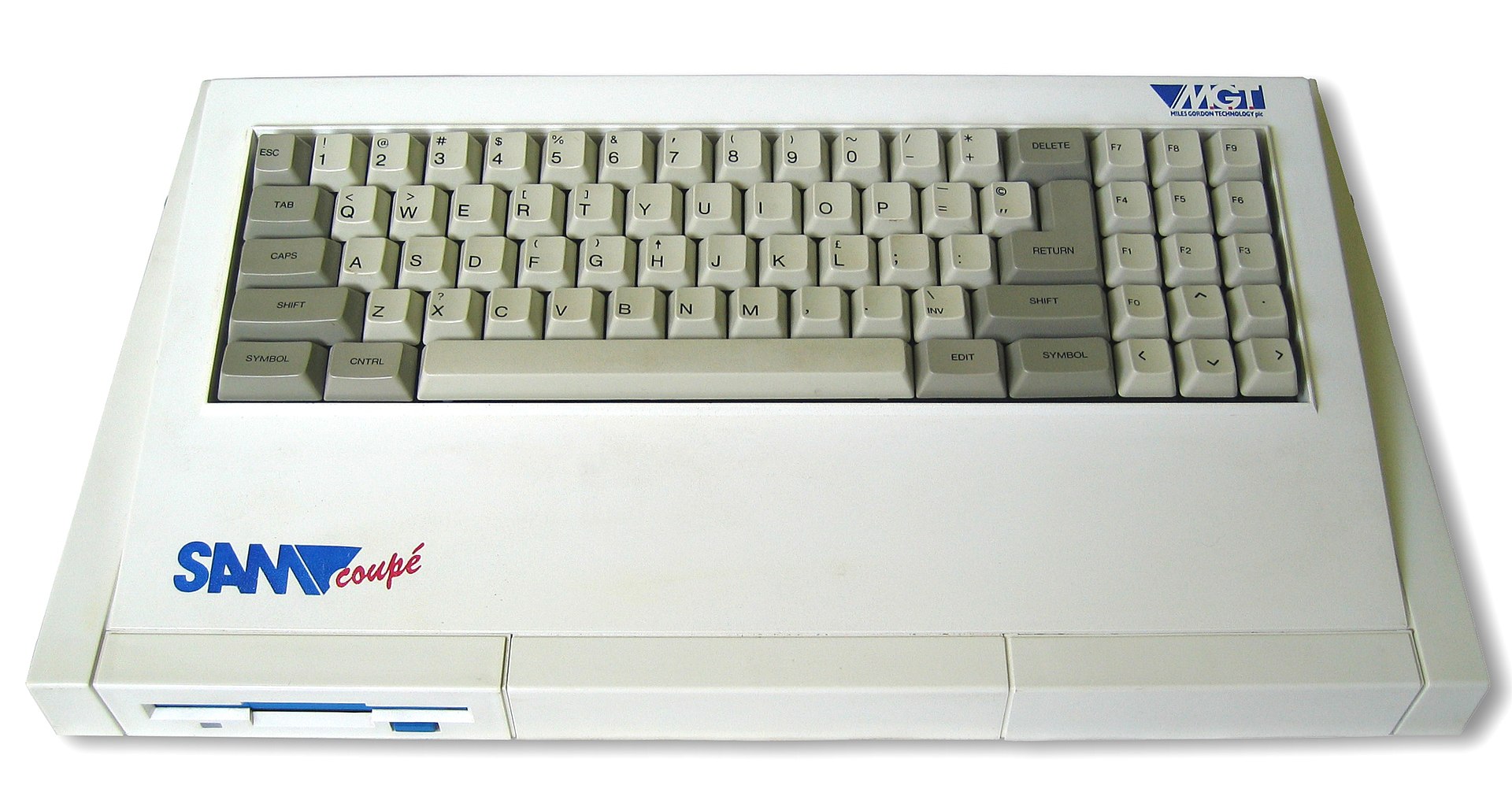

Back in the UK, 1989 saw the partial clone known as the SAM Coupé by Miles Gordon Technology (MGT). Best known for their Spectrum disk drive add-ons, they fancied a stab at the Spectrum clone market as they saw Amstrad losing interest in the Spectrum brand and unwilling to invest in another new Spectrum, allegedly for fear of it damaging sales of their own established and successful CPC rival home computer models.

Priced at £150, the SAM Coupé was intended as a “next-generation” successor machine to the Sinclair Spectrum with a faster CPU and greatly enhanced graphics, memory and sound compared to even the 128K Spectrums, while having compatibility with the majority of 48K Spectrum software (but sadly not 128K Spectrum software) via emulation but remained based on 8-bit technology. As the world had already long begun its move into the 16-bit era, it was effectively obsolete at the time of launch and was axed just 3 years later, causing the collapse of the company (twice!) in the process.

The ZX Spectrum’s legacy today

So by 1993, there was no new Spectrum compatible machine in production in the UK and this remained the case until the latter half of the 2010s when several die-hard fans of the Spectrum, including one who worked on the design of the original and another who had been working on his own project in Brazil to produce an updated Spectrum clone (TBBlue), got together to design the first true, new “official” Sinclair Spectrum in more than 2 decades. With intellectual property rights and branding agreements obtained from Sky (now the owners of Amstrad), to ensure it was branded as a Sinclair machine and remained fully compatible and not just a clean-room engineered clone, a brand-new greatly enhanced machine was designed, funded, and produced over the course of two Kickstarter campaigns (so far!).

Crucially, the Spectrum Next is hardware and software compatible with the original Spectrum machines, both 48K and 128K variants as its – now obsolete – Z80A processor is implemented using an FPGA chip instead of via emulation and specific modes exist in the firmware for each of the previous Spectrum variants, thus ensuring maximum compatibility. While its £300+ price tag means it’s not exactly cheap, for the many new abilities it offers (which are far in advance of the original Spectrum), it is priced similarly to how the original Spectrum was back in 1982, allowing for inflation.

The machines are in short supply and not widely available (and go for many times their original purchase price on eBay) but just go to demonstrate how popular the Sinclair Spectrum still is 40 years on! If there’s ever a 3rd Kickstarter for it, I’d love to back it and get one! That childhood love and urge to get a new Sinclair computer is back again!

The ZX Spectrum thus lives on, as actual new, real hardware you can buy still (sort of), as emulators on countless other computing platforms from the PC to the Raspberry Pi and it lives on in the many enthusiasts who are still writing new software for the Spectrum and Spectrum Next and those who produce an abundance of material on many Spectrum fan sites and YouTube channels, of which, one of the most remarkable and long-lasting must be Paul Jenkinson’s The Spectrum Show.

And for those with aging Spectrums in need of repair, like myself, there’s even still a way to get them fixed, as companies like Mutant Caterpillar offer a full repair and refurb service for your beloved Speccy!

40 years old and there’s life in the Spectrum still, here’s to the next 40 years!

Happy Birthday to the humble Speccy, now where’s that copy of Pacmania… 😁